I WOULD LIKE TO THANK THE NUMEROUS AMOUNT OF PEOPLE WHO

CONTRIBUTED TO THIS SERIES AND THE TREMENDOUS AMOUNT OF TIME AND

RESEARCH INVOLVED--I HOPE THE YOUNGER GENERATION HAVE TAKEN THE TIME TO

READ ABOUT THEIR HISTORY JUST AS I HOPE THOSE WHO REALLY THINK THAT GAYS

WANT 'SPECIAL NOT EQUAL' RIGHTS LEARN WHAT WE ARE FIGHTIGN FOR AND WHY

INCLUDING THOSE WHO THINK THIS IS 'RIDICULOUS'.

"Intolerable

situation"

Activity in Greenwich Village was sporadic on Monday and Tuesday,

partly due

to rain. Police and Village residents had a few altercations, as both

groups

antagonized each other. Craig Rodwell and his partner Fred Sargeant took

the

opportunity the morning after the first riot to print and distribute

5,000

leaflets, one of them reading: "Get the Mafia and the Cops out of Gay

Bars". The

leaflets called for gays to own their own establishments, for a boycott

of the

Stonewall and other Mafia-owned bars, and for public pressure on the

mayor's

office to investigate the "intolerable situation"

Not everyone in the gay community considered the revolt a positive

development. To many older gays and many members of the Mattachine

Society that had worked throughout the 1960s to promote homosexuals

as no

different from heterosexuals, the display of violence and effeminate

behavior

was embarrassing. Randy Wicker, who had marched in the first gay picket

lines

before the White House in 1965, said the "screaming queens forming

chorus lines

and kicking went against everything that I wanted people to think about

homosexuals ... that we were a bunch of drag queens in the Village

acting

disorderly and tacky and cheap." Others found the

closing of the Stonewall Inn, termed a "sleaze joint", as advantageous

to the

Village.

On Wednesday, however, The Village Voice ran reports of the

riots, written by Howard Smith and Lucian Truscott, that included

unflattering

descriptions of the events and its participants: "forces of faggotry,"

"limp

wrists" and "Sunday fag follies". A mob descended upon Christopher

Street once again and

threatened to burn down the offices of The Village Voice. Also in

the mob

of between 500 and 1,000 were other groups that had had unsuccessful

confrontations with the police, and were curious how the police were

defeated in

this situation. Another explosive street battle took place, with

injuries to

demonstrators and police alike, looting in local shops, and arrests of

five

people. The incidents on

Wednesday night lasted about an hour, and were summarized by one

witness: "The

word is out. Christopher Street shall be liberated. The fags have had it

with

oppression."

Aftermath

Photographer Kay Lahusen, seen

marching in the 1969 Annual

Reminder days after the riots. This year, some of the participants were

frustrated with the conservative approach to activism.

The feeling of urgency spread throughout Greenwich Village, even to

people

who had not witnessed the riots. Many who were moved by the rebellion

attended

organizational meetings, sensing an opportunity to take action. On July

4, 1969,

the Mattachine Society performed its annual picketing in front of Independence

Hall in Philadelphia,

called the Annual Reminder.

Organizer Craig Rodwell,

Frank

Kameny, Randy Wicker, Barbara Gittings,

and

Kay

Lahusen, who had all

participated for several years, took a bus along with other picketers

from New

York City to Philadelphia. Since 1965, the pickets had been very

controlled:

women wore skirts and men wore suits and ties, and all marched quietly

in

organized lines. This year Rodwell

remembered feeling restricted by the rules Kameny had set. When two

women

spontaneously held hands, Kameny broke them apart, saying, "None of

that! None

of that!" Rodwell, however, convinced about ten couples to hold hands.

The

hand-holding couples made Kameny furious, but they earned more press

attention

than all of the previous marches.

Participant Lilli Vincenz remembered, "It was clear that things were

changing.

People who had felt oppressed now felt empowered." Rodwell returned to New York City determined to change the established

quiet,

meek ways of trying to get attention. One of his first priorities was

planning

Christopher

Street Liberation Day.

Gay Liberation

Front

Although the Mattachine Society had existed since the 1950s, many of

their

methods now seemed too mild for people who had witnessed or been

inspired by the

riots. Mattachine recognized the shift in attitudes in a story from

their

newsletter entitled, "The Hairpin Drop Heard Around the World". When a Mattachine officer suggested an "amicable and

sweet" candlelight vigil demonstration, a man in the audience fumed and

shouted,

"Sweet! Bullshit! That's the role society has been forcing these

queens

to play." With a

flyer announcing: "Do You Think Homosexuals Are Revolting? You Bet Your

Sweet

Ass We Are!", the Gay Liberation

Front (GLF) was soon formed, the first gay organization to use "gay"

in its

name. Previous organizations such as the Mattachine

Society, the Daughters of

Bilitis, and various homophile groups had masked their purpose by

deliberately choosing obscure names.

The rise of militancy became apparent to Frank Kameny and Barbara

Gittings—who had worked in homophile organizations for years and were

both very

public about their roles—when they attended a GLF meeting to see the new

group.

A young GLF member demanded to know who they were and what their

credentials

were. Gittings, nonplussed, stammered, "I'm gay. That's why I'm here."

The GLF borrowed

tactics from and aligned themselves with black and antiwar demonstrators with the

ideal that they "could work to restructure American society". They took

on

causes of the Black Panthers, marching to the Women's

House of

Detention in support of Afeni Shakur, and

other radical New Left causes. Four

months after

they formed, however, the group disbanded when members were unable to

agree on

operating procedure.

Gay Activists

Alliance

Within six months of the Stonewall riots, activists started a

city-wide

newspaper called Gay;

they considered it necessary because the most liberal publication in the

city—The Village Voice—refused to print the word "gay" in GLF

advertisements seeking new members and volunteers. Two other

newspapers were initiated within a six-week period: Come Out!Gay

Power; the readership of these three periodicals quickly climbed to

between

20,000 and 25,000. and

GLF members organized several same-sex dances, but GLF meetings were

chaotic.

When Bob Kohler asked for clothes and money to help the homeless youth

who had

participated in the riots, many of whom slept in Christopher Park or

Sheridan

Square, the response was a discussion on the downfall of capitalism.

In late December

1969, several people who had visited GLF meetings and left out of

frustration

formed the Gay Activists

Alliance (GAA). The GAA

was to be entirely focused on gay issues, and more orderly. Their

constitution

started, "We as liberated homosexual activists demand the freedom for

expression

of our dignity and value as human beings". The GAA

developed and perfected a confrontational tactic called a zap,

where they would catch a

politician off guard during a public relations opportunity, and force

him or her

to acknowledge gay and lesbian rights. City councilmen were zapped, and

Mayor John Lindsay was

zapped

several times—once on television when GAA members made up the majority

of the

audience.

Raids on gay bars had not stopped after the Stonewall riots. In March

1970,

Deputy Inspector Seymour Pine raided the Zodiac and 17 Barrow Street. An

after-hours gay club with no liquor or occupancy licenses called The

Snake Pit

was soon raided, and 167 people were arrested. One of them was an

Argentinian

national so frightened that he might be deported as a homosexual that he tried to escape the

police precinct by jumping out a two-story window, impaling himself on a

14-inch

(36 cm) spike fence. The New York

Daily News printed a graphic photo of the young man's impalement on

the

front page. GAA members organized a march from Christopher Park to the

Sixth

Precinct in which hundreds of gays, lesbians, and liberal sympathizers

peacefully confronted the TPF.Democratic

Party and

Congressman Ed Koch sent pleas to

end raids on gay bars in the city They

also sponsored a letter-writing campaign to Mayor Lindsay in which the

Greenwich

Village

The Stonewall Inn lasted only a few weeks after the riot. By October

1969 it

was up for rent. Village residents surmised it was too notorious a

location, and

Rodwell's boycott discouraged business.

Gay Pride

Christopher Street Liberation Day on June 28, 1970 marked the first

anniversary of the Stonewall riots with an assembly on Christopher

Street and

the first Gay Pride march in U.S. history, covering the 51 blocks to Central Park. The

march took less than half the

scheduled time due to excitement, but also due to wariness about walking

through

the city with gay banners and signs. Although the parade permit was

delivered

only two hours before the start of the march, the marchers encountered

little

resistance from onlookers. The New York

Times Reporting by The Village Voice was positive, describing "the

out-front

resistance that grew out of the police raid on the Stonewall Inn one

year

ago" reported (on the front page) that the marchers took up the

entire

street for about 15 city blocks.

There was little open animosity, and some bystanders applauded

when a

tall, pretty girl carrying a sign "I am a Lesbian" walked by. – The

New

York Times coverage of Gay Liberation Day, 1970

Gay Pride marches took place simultaneously in Los Angeles and Chicago. The next year,

Gay Pride marches took place in Boston,

Dallas,

Milwaukee,

London,

Paris, West

Berlin, and Stockholm. By

1972 the participating cities included Atlanta, Buffalo, Detroit,

Washington D.C.,

Miami,

and Philadelphia.

Frank Kameny soon realized the pivotal change brought by the

Stonewall riots.

An organizer of gay activism in the 1950s, he was used to persuasion,

trying to

convince heterosexuals that gay people were no different than they were.

When he

and other people marched in front of the White House, the State

Department and

Independence Hall only five years earlier, their objective was to look

as if

they could work for the U.S. government. Ten people

marched with Kameny then, and they alerted no press to their intentions.

Although he was stunned by the upheaval by participants in the Annual

Reminder

in 1969, he later observed, "By the time of Stonewall, we had fifty to

sixty gay

groups in the country. A year later there was at least fifteen hundred.

By two

years later, to the extent that a count could be made, it was

twenty-five

hundred."

Similar to Kameny's regret at his own reaction to the shift in

attitudes

after the riots, Randy Wicker came to describe his embarrassment as "one

of the

greatest mistakes of his life"The

image of gays retaliating against police, after so many years of

allowing such

treatment to go unchallenged, "stirred an unexpected spirit among many

homosexuals". Kay

Lahusen, who photographed the marches in 1965, stated, "Up to 1969, this

movement was generally called the homosexual or homophile movement....

Many new

activists consider the Stonewall uprising the birth of the gay

liberation

movement. Certainly it was the birth of gay pride on a massive scale."

Legacy

Unlikely community

Within two years of the Stonewall riots there were gay rights groups

in every

major American city, as well as Canada, Australia, and Western Europe.[124] People who

joined activist organizations after the riots had very little in common

other

than their same-sex

attraction. Many who arrived at

GLF or GAA meetings were taken aback by the number of gay people in one

place. Race, class,

ideology, and gender became frequent obstacles in the years after the

riots.

This was illustrated during the 1973 Stonewall rally when, moments after

Barbara Gittings exuberantly praised the diversity of the crowd, feminist activist Jean

O'Learytransvestitesdrag queens in

attendance. During

a speech by O'Leary, in which she claimed that drag queens made fun of

women for

entertainment value and profit, Sylvia Rivera and

Lee Brewster jumped on the

stage and shouted "You go to bars because of what drag queens did for

you, and

these bitches tell us to quit being ourselves!"[ Both the drag

queens and lesbian feminists in attendance left in disgust. protested what

she perceived as the mocking of women by

and

O'Leary also worked in the early 1970s to exclude transvestites from

gay

rights issues because she felt that rights for transvestites would be

too

difficult to attain. Sylvia Rivera left gay activism in the 1970s to

work on

issues for transgender people and transvestites. The initial

disagreements

between participants in the movements, however, often evolved after

further

reflection. O'Leary later regretted her stance against the drag queens

attending

in 1973: "Looking back, I find this so embarrassing because my views

have

changed so much since then. I would never pick on a transvestite now.""It

was horrible. How could I work to exclude transvestites and at the same

time

criticize the feminists who were doing their best back in those days to

exclude

lesbians?"

O'Leary was referring to the Lavender Menace,

a description by second wave

feminist Betty Friedan for

attempts

by members of the National

Organization for Women (NOW) to distance themselves from the perception of NOW as a haven for

lesbians.

As part of this process, Rita Mae Brown and other lesbians who had been

active in NOW were forced out. They staged a protest in 1970 at the

Second

Congress to Unite Women, and earned the support of many NOW members,

finally

gaining full acceptance in 1971.

The growth of lesbian feminism in the 1970s at times so

conflicted with the gay liberation movement that some lesbians refused

to work

with gay men. Many lesbians found men's attitudes patriarchal and

chauvinistic,

and saw in gay men the same misguided notions about women as they saw in

heterosexual men. The issues most important to gay men—entrapment and public

solicitation—were not shared

by lesbians. In 1977 a Lesbian Pride Rally was organized as an

alternative to

sharing gay men's issues, especially what Adrienne Rich termed "the violent,

self-destructive world of the gay bars" Veteran gay activist Barbara Gittings chose to work in the gay rights

movement,

rationalizing "It's a matter of where does it hurt the most? For me it

hurts the

most not in the female arena, but the gay arena."

Throughout the 1970s gay activism had significant successes. One of

the first

and most important was the "zap" in May 1970 by the Los Angeles GLF at a

convention of the American

Psychiatric

Association (APA). At a conference on behavior

modification, during a film

demonstrating the use of electroshock

therapy to decrease same-sex

attraction, Morris Kight When

the APA invited gay activists to speak to the group in 1972, activists

brought

John E. Fryer, a

gay

psychiatrist who wore a mask, because he felt his practice was in

danger. In

December 1973—in large part due to the efforts of gay activists—the APA

voted

unanimously to remove homosexuality from the Diagnostic

and Statistical

Manual. and GLF members in the audience interrupted the film with shouts of

"Torture!"

and "Barbarism!" They

took over the microphone to announce that medical professionals who

prescribed

such therapy for their homosexual patients were complicit in torturing

them.

Although 20 psychiatrists in attendance left, the GLF spent the hour

following

the zap with those remaining, trying to convince them that homosexuals

were not

mentally ill.

Gay men and lesbians came together to work in grassroots political

organizations responding to

organized resistance in 1977. A coalition of conservatives named Save Our Children staged a campaign to repeal a civil rights ordinance in Dade County,

Florida.

Save Our Children was successful enough to influence similar repeals in

several

American cities in 1978. However, the same year a campaign in California

called

the Briggs

Initiative, designed to force the dismissal of homosexual public

school

employees was defeated. Reaction to the

influence of Save Our Children and the Briggs Initiative in the gay

community

was so significant that it has been called the second Stonewall for many

activists, marking their initiation into political participation.

[ Rejection of

gay

subculture

The Stonewall riots marked such a significant turning point that many

aspects

of prior gay and lesbian

subculture, such as bar culture formed from decades of shame and

secrecy,

were forcefully ignored and denied. Historian Martin Duberman writes, "The decades preceding

Stonewall ... continue to be regarded by most gays and lesbians as some

vast

neolithic wasteland". Historian Barry

Adam notes, "Every social movement must choose at some point what to

retain and

what to reject out of its past. What traits are the results of

oppression and

what are healthy and authentic?" In

conjunction with the growing feminist movement of the early 1970s, roles

of butch and femme that

developed in lesbian bars in the 1950s and 1960s were rejected, because

as one

writer put it: "all role playing is sick". Lesbian

feminists considered the butch roles as archaic imitations of masculine

behavior. Some women,

according to Lillian

Faderman, were eager to shed the roles they felt forced into

playing. The

roles returned for some women in the 1980s, although they allowed for

more

flexibility than before Stonewall.

Author Michael Bronski highlights the "attack on pre-Stonewall

culture",

particularly gay pulp

fiction for men, where the

themes often reflected ambivalence about being gay or self-hatred. Many

books

ended unsatisfactorily and drastically, often with suicide, and writers

portrayed their gay characters as alcoholics and deeply unhappy. These

books,

which he describes as "an enormous and cohesive literature by and for

gay

men", have not been

reissued and are lost to later generations. Dismissing the reason simply

as

political correctness, Bronski writes, "gay liberation was a youth

movement

whose sense of history was defined to a large degree by rejection of the

past".

Lasting impact

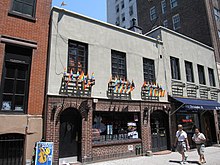

The Stonewall, a bar in part of the

building where

the Stonewall InnNational

Historic

Landmark. was

located. The building and the surrounding streets have been declared a

The riots spawned from a bar raid became a literal example of gays

and

lesbians fighting back, and a symbolic call to arms for many people.

Historian

David Carter remarks in his book about the Stonewall riots that the bar

itself

was a complex business that represented a community center, an

opportunity for

the Mafia to blackmail its own customers, a home, and a place of

"exploitation

and degradation". The true legacy

of the Stonewall riots, Carter insists, is the "ongoing struggle for

lesbian,

gay, bisexual, and transgender equality".Historian

Nicholas Edsall writes,

Stonewall has been compared to any number of acts of radical protest

and

defiance in American history from the Boston Tea Party on. But the best

and

certainly a more nearly contemporary analogy is with Rosa Parks'

refusal to move to the back of the bus

in Montgomery, Alabama, in December 1955, which sparked the modern civil

rights

movement. Within months after Stonewall radical gay liberation groups

and

newsletters sprang up in cities and on college campuses across America

and then

across all of northern Europe as well.

Before the rebellion at the Stonewall Inn, homosexuals were, as

historians

Dudley Clendinen and Adam

Nagourney write,

a secret legion of people, known of but discounted, ignored, laughed

at or

despised. And like the holders of a secret, they had an advantage which

was a

disadvantage, too, and which was true of no other minority group in the

United

States. They were invisible. Unlike African Americans, women, Native

Americans,

Jews, the Irish, Italians, Asians, Hispanics, or any other cultural

group which

struggled for respect and equal rights, homosexuals had no physical or

cultural

markings, no language or dialect which could identify them to each

other, or to

anyone else ... But that night, for the first time, the usual

acquiescence

turned into violent resistance ... From that night the lives of millions

of gay

men and lesbians, and the attitude toward them of the larger culture in

which

they lived, began to change rapidly. People began to appear in public as

homosexuals, demanding respect.

Historian Lillian

Faderman calls the riots the "shot heard round the world",

explaining, "The

Stonewall Rebellion was crucial because it sounded the rally for that

movement.

It became an emblem of gay and lesbian power. By calling on the dramatic

tactic

of violent protest that was being used by other oppressed groups, the

events at

the Stonewall implied that homosexuals had as much reason to be

disaffected as

they."

Joan Nestle started

the

Lesbian

Herstory Archives in 1975, and credits "its creation to that night

and the

courage that found its voice in the streets".

Cautious, however, not to attribute the start of gay activism to the

Stonewall

riots, Nestle writes,

I certainly don't see gay and lesbian history starting with Stonewall

... and

I don't see resistance starting with Stonewall. What I do see is a

historical

coming together of forces, and the sixties changed how human beings

endured

things in this society and what they refused to endure.... Certainly

something

special happened on that night in 1969, and we've made it more special

in our

need to have what I call a point of origin ... it's more complex than

saying

that it all started with Stonewall.

The events of the early morning of June 28, 1969 were not the first

instances

of homosexuals fighting back against police in New York CityLos Angeles and Chicago,

but similarly marginalized people started the

riot at Compton's Cafeteria in 1966, and another riot responded to a

raid on Los

Angeles' Black Cat

Tavern in 1967.[ However, several

circumstances were in place that made the Stonewall riots memorable. The

location of the raid was a factor: it was across the street from The

Village

Voice offices, and the narrow crooked streets gave the rioters

advantage

over the police. Many

of the participants and residents of Greenwich Village were involved in

political organizations that were effectively able to mobilize a large

and

cohesive gay community in the weeks and months after the rebellion. The

local

press and national gay press covered the event extensively. The most

significant

facet of the Stonewall riots, however, was the commemoration of them in Christopher

Street Liberation Day, which grew into the annual Gay Pride and

elsewhere. Not only had the

Mattachine Society been active in major cities such as events

around the

world.

The middle of the 1990s was marked by the inclusion of bisexuals as a

represented group within

the gay community when they successfully sought to be included on the

platform

of the 1993 March

on Washington for Lesbian, Gay and Bi Equal Rights and Liberation.

Despite

also requesting to be included, transgender people were instead afforded

trans-inclusive language on the march's list of demands.The

transgender

community continued to find itself simultaneously welcome and at odds

with the

gay community as attitudes about binary and fluid sexual orientation and

gender

developed and came increasingly into conflictIn

1994, New York City celebrated "Stonewall 25" with a march that went

past the United

Nations Headquarters and

into Central Park.

Estimates put the attendance at 1.1 million people. Sylvia Rivera

led an alternate march in New York City in 1994 to protest the exclusion

of

transgender people from the events. Attendance at

Gay Pride events has grown substantially over the decades. Most large

American

cities have some kind of Pride demonstration, as do most large cities

around the

world. Pride events in some cities mark the largest annual celebration

of any

kind. The growing

trend towards commercializing marches into parades—with events receiving

corporate sponsorship—has caused concern about taking away the autonomy

of the

original grassroots demonstrations that put inexpensive activism in the

hands of

individuals.

In June 1999 the U.S.

Department of the

Interior designated 51 and 53 Christopher Street, the street itself,

and the

surrounding streets as a National

Historic Landmark, the

first of significance to the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender

community.

In a dedication ceremony, Assistant Secretary of the Department of the

Interior

John

Berry stated, "Let it forever

be remembered that here—on this spot—men and women stood proud, they

stood fast,

so that we may be who we are, we may work where we will, live where we

choose

and love whom our hearts desire."

On June 1, 2009, President Barack Obama declared June 2009 Lesbian, Gay,

Bisexual, and Transgender Pride Month, citing the riots as a reason to

"commit

to achieving equal justice under law for LGBT Americans". The year marked

the 40th anniversary of the riots, giving journalists and activists

cause to

reflect on progress made since 1969. Frank Rich in The

New York Times noted that

no federal legislation exists to protect the rights of gay Americans. An

editorial in the Washington Blade compared the scruffy,

violent activism during and following the Stonewall riots to the

lackluster

response to failed promises given by President Obama; for being ignored,

wealthy

LGBT activists reacted by promising to give less money to Democratic

causes.

SEE YOU IN 2011 IN THE MERRY MONTH

OF JUNE WHEN WE CELEBRATE GAY PRIDE AND REMEMBER STONEWALL AGAIN!