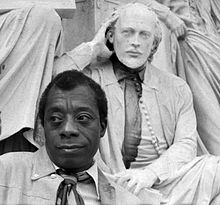

I met James Baldwin 3 important times in

my life. The first time was through his writing when I read his books

"Go Tell It On The Mountain" and "Giovanni's Room". Both were explosive

books that talked about being gay openly, and sexually, explicitly at a

time it was talked about only in shadows. It was also a time I was

exploring my own sexuality and ceratinly helped me understand it more.

A

few years later when I was going with Paul Orr, a producer of the Jack

Paar TV show, he took me backstage of "Blues For Mr. Charlie", a play by

Baldwin, making its debut on Broadway. The last time was in 1969, just

before I was leaving to live in Memphis, when he was at a party I was

attending. He had just flown in from Paris, was very involved with the

civil rights movement and this was a fund raising party. Somehow I found

myself in a group consisting of Baldwin and Marlon Brando and about 6

other people. Though I was becoming an accomplished public speaker, was

33 and far from shy I stood there listening for 45 minutes without

saying a word!

Literary career

In 1953, Baldwin's first novel, Go Tell It on the

Mountain, an autobiographical bildungsroman, was published. Baldwin's first

collection of essays, Notes of a Native Son appeared two

years later. Baldwin continued to experiment with literary forms throughout his

career, publishing poetry and plays as well as the fiction and essays for which

he was known.

Baldwin's second novel, Giovanni's Room, stirred controversy when

it was first published in 1956 due to its explicit homoerotic content.[8] Baldwin was again

resisting labels with the publication of this work:[9] despite the

reading public's expectations that he would publish works dealing with the

African American experience, Giovanni's Room is exclusively about white

characters.[9] Baldwin's

next two novels, Another CountryTell Me How Long the

Train's Been Gone, are sprawling, experimental works[10] dealing with black and white characters and with heterosexual, homosexual, and

bisexual characters.[11] These novels

struggle to contain the turbulence of the 1960s: they are saturated with a sense

of violent unrest and outrage. and

Baldwin's lengthy essay Down

at the Cross (frequently called The Fire Next Time after the title of

the book in which it was published)[12] similarly showed

the seething discontent of the 1960s in novel form. The essay was originally

published in two oversized issues of The New Yorker and landed Baldwin on the

cover of Time magazine in 1963 while Baldwin was touring the South speaking about the restive

Civil Rights movement. The essay talked about the uneasy relationship between

Christianity and the burgeoning Black Muslim movement. Baldwin's next

book-length essay, No Name in the Street, also discussed

his own experience in the context of the later 1960s, specifically the

assassinations of three of his personal friends: Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King,

Jr.

Baldwin's writings of the 1970s and 1980s have been largely overlooked by

critics. The assassinations of black leaders in the 1960s, Eldridge Cleaver's

vicious homophobic attack on Baldwin in Soul on Ice, and Baldwin's return

to southern France contributed to the sense that he was not in touch with his

readership. Always true to his own convictions rather than to the tastes of

others, Baldwin continued to write what he wanted to write. His two novels

written in the 1970s, If Beale Street Could Talk and

Just Above My

Head, placed a strong emphasis on the importance of black families, and

he concluded his career by publishing a volume of poetry, Sonny's Blues, as

well as another book-length essay, The Evidence of Things Not

Seen, which was an extended meditation inspired by the Atlanta Child Murders of the early 1980s.

Baldwin's

expatriation

During his teenage years in Harlem and Greenwich Village, Baldwin began to

recognize his own homosexuality. In 1948, disillusioned by American prejudice

against blacks and homosexuals, Baldwin left the United States and departed to

Paris, France. His flight was not just a

desire to distance himself from American prejudice. He fled in order to see

himself and his writing beyond an African American context and to be read as not

"merely a Negro; or, even, merely a Negro writer" Also, he left the United States desiring to come to terms with his sexual

ambivalence and flee the hopelessness that many young African American men like

himself succumbed to in New York.

In Paris, Baldwin was soon involved in the cultural radicalism of the Left

Bank. His work started to be published in literary anthologies, notably

Zero , which was edited by

his friend Themistocles Hoetis and which had already

published essays by Richard Wright.

He would live as an expatriate in France for most of his later life. He

would also spend some time in Switzerland and Turkey. During his life and after it, Baldwin would be seen not only as an influential

African American writer but also as an influential exile writer, particularly

because of his numerous experiences outside of the United States and the impact

of these experiences on Baldwin's life and his writing.

Social and political

activism

After his return to the United States from France and a subsequent trip to

the South in 1962, Baldwin aligned himself more closely with the ideals of the

Congress of Racial Equality (CORE)

and the Student Nonviolent

Coordinating Committee (SNCC). In 1963 he conducted a lecture tour of the

South for CORE, traveling to locations like Durham and Greensboro, North

Carolina and New Orleans, Louisiana. During the tour, he lectured to students,

white liberals, and anyone else listening about his racial ideology, an

ideological position between the "muscular approach" of Malcolm X and the nonviolent program of Martin Luther King Jr..

At this time, Baldwin threw himself into the civil rights movement. In 1963,

along with prominent figures like Lorraine Hansberry and Harry Belafonte and

other civil rights figures, Baldwin met with then Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy to discuss the moral implications of the civil rights movement. Although most of

the attendees of this meeting left feeling "devastated," the meeting was an

important one in voicing the concerns of the civil rights movement and it

provided exposure of the civil rights issue not just as a political issue but

also as a moral issue.. Baldwin also made

a prominent appearance at the Civil Rights March on

Washington, D.C. on August 28th, 1963, also with Belafonte, as well as with

long time friends Sidney

Poitier and Marlon

Brando.

Inspiration and

relationships

Inspiration and

relationships

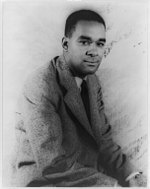

One source of support came from an admired older writer Richard

Wright, whom he called "the greatest black writer in the world". Wright and

Baldwin became friends for a short time and Wright helped him to secure the

Eugene F. Saxon Memorial Award. Baldwin titled a collection of essays

Notes of

a Native Son, in clear reference to Wright's novel Native Son. However,

Baldwin's 1949 essay "Everybody's Protest Novel" ended the two authors'

friendship[15]Native Son, like Harriet Beecher

Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin, lacked credible

characters and psychological complexity. However, during an interview with

Julius Lester,[16] because Baldwin

asserted that Wright's novel Baldwin explained

that his adoration for Wright remained: "I knew Richard and I loved him. I was

not attacking him; I was trying to clarify something for myself".

1949 was also the year he met and fell in love with Lucien

Happersberger. The boy was a seventeen-year-old runaway, and the two became

very close, until Happersberger's marriage three years later, an event that left

Baldwin devastated.[17]

Another major influence on Baldwin's life was the African-AmericanBeauford

Delaney. In The Price of the Ticket (1985),

Baldwin describes Delaney as "the first living proof, for me, that a black man

could be an artist. In a warmer time, a less blasphemous place, he wou painter

became, for me, an example

of courage and integrity, humility and passion. An absolute integrity: I saw him

shaken many times and I lived to see him broken but I never saw him bow".

Baldwin was a close friend of the singer, pianist and civil rights activist

Nina Simone. Together with

Langston Hughes and

Lorraine

Hansberry, Baldwin was responsible for making Simone aware of the civil

rights movement that was forming at that time to fight racial inequality. He

also provided her with literary references that influenced her later work.

Baldwin also had an influence on the work of the French painter Philippe Derome who he

met in Paris at the beginning of the 1960s.

Maya Angelou called

Baldwin her "friend and brother", and credited him for "setting the stage" for

the writing of her 1969 autobiography, I Know Why the Caged Bird

Sings.

There is a couple there I liked to read if I can find it.

Tell it on the Mountain and One Day When I Was lost.

Matter of fact will check with the library but believed that they will have none of his books in this town.But nonetheless they will find it for me and are good in doing so.Thank you for the article.