The Mary Rose was built at Portsmouth between 1509 and 1511. Named for Henry VIII's favourite sister, Mary Tudor, later queen of France, the ship was part of a large build-up of naval force by the new king in the years between 1510 and 1515. Warships, and the cannon they carried, were the ultimate status symbol of the 16th century, and an opportunity to show off the wealth and power of the king abroad.

In addition Henry was well aware that his right to the throne was open to challenge, and that sea-borne invasions, such as the one his father had staged from France, in order to claim the English throne only three decades earlier, were easy for his enemies to organise. To meet the danger he built up his fleet, fortified the obvious landing places, and wiped out those with any claim to the succession.

Henry's early shipbuilding programme culminated with the massive Henry Grace a Dieu of 1500 tons. While the Mary Rose was smaller, initially rated at 600 tons, she remained the second most powerful ship in the fleet and a favourite of the king. She was considered to be a fine sailing ship, operating in the Channel to keep up links with the last English possessions around Calais. She was a carrack, equipped to fight at close range.

As built, the Mary Rose was intended to close with her enemies, fire her guns, come alongside to allow the soldiers she was carrying to board the enemy ship, supported by a hail of arrows, darts and quick-lime, and to capture it by hand-to-hand fighting. Aside from the use of small guns, little had changed in the design of warships since Edward III's victory at Sluys in 1340. The only heavy guns were mounted low in the stern, and were mainly used to bombard shore positions.

Then, along with many other big ships, the Mary Rose was rebuilt in the 1530s. Her 1536 rebuild transformed her into a 700-ton prototype galleon, with a powerful battery of heavy cannon, capable of inflicting serious damage on other ships at a distance. The high castles were cut down, decks strengthened, and she was armed with heavy guns, with 15 large bronze guns, 24 wrought-iron carriage guns and 52 smaller anti-personnel guns. The Mary Rose now had the firepower to engage the enemy on any bearing, and conduct a stand-off artillery battle. Some of the guns were mounted on advanced naval gun carriages, which made them far easier to handle and move on a crowded gun deck.

The new emphasis on artillery reflected the mastery of gun founding in England, another development pushed by Henry VIII. It also reflected the need for a naval force to defend the kingdom against European rivals, as Henry adopted his radical new foreign policy, based on religious grounds. The resources for the new cannon, ships and coastal forts came from the seizure and sale of monastic estates. The main impetus behind the rebuild was the fear of French galleys that had defeated the English fleet, led by the Mary Rose, in Brest Roads in 1513. The mobility, heavy bow guns and small target area of the French galleys made them very dangerous opponents.

As rebuilt, the Mary Rose was expected to fight using all her guns, sailing down towards the enemy, firing the ahead weapons, before turning to present one broadside, the stern, the other broadside and then making off to reload, while other ships took her place. This was a lengthy process. The Mary Rose emphasised ahead and stern fire, with close-range stone-shot-firing weapons on the broadside. Two of her best bronze guns were mounted in the stern castle but bore almost directly ahead, just clearing the bow structure. As rebuilt the Mary Rose had a crew of 185 soldiers, 200 seamen and 30 gunners. In addition to cannon they were equipped with 50 handguns, 250 longbows, 300 pole arms, 480 darts to throw from the fighting tops and a wealth of arrows. While the cannon were the main weapons, close-quarters fighting was also expected.

On the evening of 19th July 1545, Mary Rose led the English fleet out of Portsmouth harbour, under the watchful eye of King Henry, to engage the advancing French galleys. Having outrun the rest of the fleet, and coming under fire, she put about, both to fire her broadside guns, and to wait for support, when a sudden gust of wind pressed her over. As her low gun-ports had not been closed, she quickly filled and sank.

A major cause of her loss was the anxiety caused by the advancing galleys. Most of her crew were drowned because she was rigged with boarding netting, to stop the enemy entering, and this trapped the men on deck, so that only a handful, working aloft, survived. While her loss was accidental, it emphasised how difficult it was to use these transitional ships.

At the time of her loss the Mary Rose was obsolescent. Her type was too cumbersome and slow to meet the challenge of galleys. The mixed battery of medium- and short-range weapons was hard to combine effectively, and this type of ship became overcrowded with sailors and soldiers. Henry had already developed a new ship type, armed entirely with heavy guns, and far more nimble under sail. Within three decades this type had grown into the galleons that defeated the Spanish Armada.

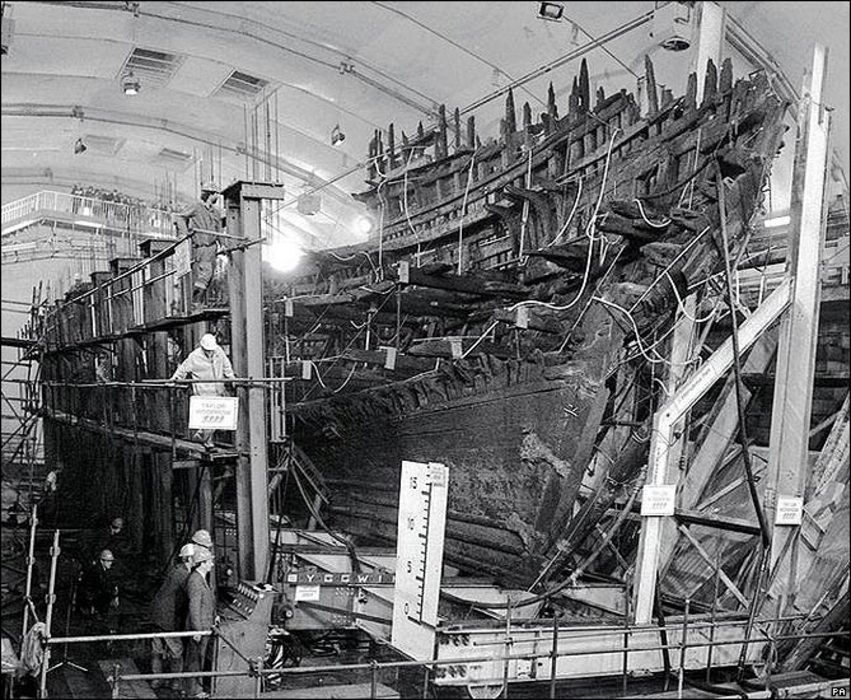

Attempts to raise the Mary Rose failed, although some of her guns were lifted at the time. Others were taken up in the 1830s, but the site was then lost, and serious investigation only began over a century later, in the 1970s. After a major archaeological investigation, the remaining half of the ship was lifted from the sea-bed on 11th October 1982, and is now undergoing conservation, along with over 22,000 artefacts found on board, at Portsmouth. This major project has provided a unique opportunity to understand the ship, her weapons, equipment, crew and stores.

The first picture above, is TheMary Rose in 'dry dock' and the next is a painting of her (don't know if this a contemporary likenes or not).

I had intended to have the dry dock pic, at the end of this post, but it displayed it self at the top & I don't know 'how' to alter it LOL, so there it can stay! LOL