I enjoyed reading this since we worked and lived in Death Valley in 1980. I added the photos for you to see the beauty and hope you will enjoy this as much as I did. Ana

A Poet in Death Valley

Remembering Miroslav Holub.

| Death Valley the Furnace Creek Visitor Center & Museum. |

In the

afternoon, after a stop at the Furnace Creek Visitor Center to pose a

few questions about the locals—Holub’s deadpan reference to the lizard

population—we drove through the dry vastness of the Valley, the vault

of blue above.

“What do you think about angels, Miroslav?” I asked. “Do you believe in some kind of spiritual creature?”I imagined the plentiful side-blotched lizards listening in.“Angels, they are present in the poems. But,” he said, “they are not required to save anyone.” “And the ‘so-called’ soul?” I asked, as I’d heard him phrase

it. Though the two entities existed hand-in-glove in my upbringing, I

could hear in Miroslav’s pause that we’d made a distinct turn of

subject. Yes, the soul, too, was present, at times connected to painful

situations.

In “Crush Syndrome,” as translated by David Young and Dana

Hábová, the soul is connected to the body but is not of the body. After

the speaker’s hand is crushed, he recognizes that he indeed has a soul,

that it’s “soft, with red stripes, / and it want[s] to be wrapped in

gauze.” The soul is attended to at the clinic, grasping with its

“mandibles” and then appearing as a being of “whitish crystal” with a

“grasshopper’s head.” By poem’s end, the soul rests as a “scar,

scarcely visible.” Here, as in other of his poems and essays written

over four decades, the soul has its own desires and abilities.

Similarly, at the close of “Creative Writing,” composed in Holub’s last

year, and as we translated it, the aging woman who aspires to

permanence possesses a “fluid soul.” In Holub’s cosmic verse, the

individual soul is a changeable entity, unpredictable and as vulnerable

to experience as its host.

* * *

I’d flown into Ontario, California, the closest airport to

where Holub was a writer in residence for a semester at Pitzer College

in 1985. A former student, friend, and

sometimes translator, I’d come to visit the Czech immunologist and

poet. But when I arrived, he wasn’t there at the gate to greet me. So I

waited. Nearly two hours later, he rushed in.

“Why are you still here?” he half demanded, half apologized. I told him I’d decided to wait, in case something had happened. If he didn’t show, I’d take a taxi to his house. He nodded in approval; then his mouth grew tight. “My Gott.

I messed it up. Sorry.” The “my” was elongated, “sorry” was clipped.

“Messed” received the greatest emphasis. For one who caused a mistake,

including himself, Holub had little patience. He had gone to the wrong

airport. We walked to the rental car.

During that April week in Southern California we logged two

thousand miles: from Venice Beach with its roving hucksters and

rollerbladers in short-shorts to Joshua Tree National Forest and its

yucca, its fire-topped ocotillo, and views of the San Andreas Fault.

Back in Claremont midweek, Holub taught his poetry seminar and I sat

in, jotting down many of his pithy observations: “the adjective is not

key; it’s simply an ornament.” And, “a poetry book is not a bag

containing poems, just like the body is not a bag containing bones. The

book has a structure. You must be aware of it.”

I was assembling my own collection, and Holub carved out time

to comment on my ripening poems: too much description here. You’ve

avoided overstatement at least. What’s your point? Indeed, as poets,

our own work was radically different. As Holub characterized our styles

in those days: “I want poetry to be a knife; yours is a caress.”

: www.davidyoungpoet.com/page9a.html

I can see Miroslav that first Sunday in the Valley—and this

fading photograph in my hand helps me to do this—looking pleased and

vigorous in his sage-colored, button-down shirt, neatly tucked into

PermaCrease slacks. Behind him, afternoon shadows cover the scrubby

hills partway while clouds gather on the horizon. He’d been many places

in the world, and still he had revolutions and revisions of the map

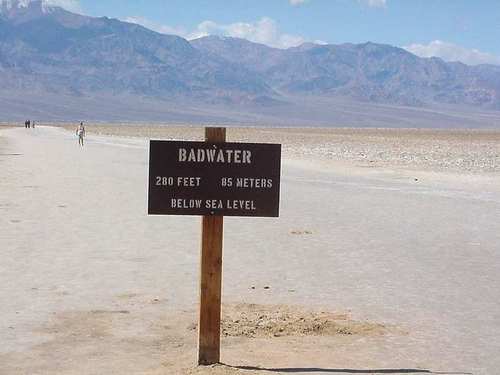

before him. Earlier that weekend in Death Valley, his interest lay with

the algae and invertebrates that inhabited the Badwater Pond and had

adapted to the extremes of temperature and saline. Surrounded by miles

of crusty salt flats, we craned our necks at the SEA LEVEL sign high in the rocky cliffs. For those few moments, as we perspired

in the heat and fought the sun’s glare, we considered our world from -282 feet.

Did he know of the Death Valley spadefoot toads—not true

toads, he would have ferreted out—that wait underground in a dehydrated

state for months, popping up after sufficient rain and bleating like

sheep? The “real deep surprises,” he’d offered, “come in the sciences.”

In the mid-sixties, as part of a collective project, Holub discovered

that the lymphocyte is the key cell of the entire immune system. The

path to that discovery was forged by something beyond the working

hypothesis, exacting methods, and repeatability of the results. It

included, as he recounts in his essay “The Discovery: An Autopsy,” as

translated by David Young and Catarina Vocadlova, a feel for his

material—“the lymphocyte, with its ability to transform itself, and

with its limitations.”

Many years later, when I returned to Death Valley I thought of

Holub in the last years of his life, as travel became increasingly

difficult for him because of a degenerative hip condition and

unpredictable bleeding from the eye. Receiving awards and giving

readings, he pressed on, to Pescara and Wellington and Hong Kong and

beyond, his urge to ask, to see: unquenchable.

As I stared across a

wooden borax wagon at the sweep of the land, the cool wind picked up. A

sudden, barely discernable moisture was present in the air. A few

people scurried toward their trucks and suvs. I scanned the sky. There it was, a rose-gray moving mass—verga, the rain that is visible above but never touches the earth.

the rain that is visible above but never touches the earth.

Death Valley Photoshttps://www.pdphoto.org/index.php.

Miroslav Holub in Death Valley Photo by Rebekah Bloyd

verga frux.net/deathvalley06.html

Miroslav Holub poetryandpoetsinrags.blogspot.com/2007_07_01_.

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/journal/article.html?id=237074

excerpt

Writing

about the future

Talk

given to the fourth Freelance Journalists, Artists and Photographers

conference of the Media, Entertainment and Arts Alliance, Sydney,

April 28, 2001

https://www.metafuture.org/articlesbycolleagues/rosaleenlove/writingthefuture.htm

"Conscious

evolution is where

biological evolution meets cosmic evolution.

Some

Humanity 3000 participants were enthusiasts for a cosmic spirituality in which a feeling for the universe is the

key to both personal and planetary salvation.

Some

participants went straight to the an event roughly four billion years

from now, when the planet earth comes to an end, swallowed up by the

sun as it flares up in the last stage of its existence. They saw it as

a human imperative to leave earth, well before it dies, to venture

forth into the solar system and beyond to keep life of some kind

keeping on. They see humans co-evolving with the universe, and with

machines, in order to accomplish this tremendous task.

More

realistically, just sticking to our own planet, I like what the

Czech immunologist and poet, Miroslav Holub (1923-1998) had to say.

Holub saw himself as a

unit of something bigger,

which he called ‘genome’ rather than ‘spirit’. His individual genome was the sum total of all the genes in his

body, yet also shared in the genetic process of all life. Holub saw

his life as a continuous part of an evolutionary whole which stretched

from the past history of life on earth into its future. He placed

himself before the genome in a spirit of humility; ‘we are not the

aim of the process’.

In

his poem, ‘The root of the matter’, Holub wrotes: ‘the root of

the matter is not/in the matter itself and often/not/in our hands.’ Where is the darkness, he asks? Where is the uncertainty? The

scientist, in the spirit of humility, is asking what the individual

can do in a world where nothing is one hundred percent sure.

Holub

imagined a kind of biological or genetic supraconsciousness, where the

biologist finds meaning in life by accepting responsibility for the planet

as a whole, and as a viable system. The

immunologist plays a part in this process of stewardship through seeking

to control the disease process in plants, humans, and other animals. In

talking about a genetic supraconsciousness, Holub goes way beyond the

‘here and now’ of present biological knowledge, but does so in a

spirit of humility before human ignorance of the whole. I

like his vision."

When the bees fell silent by Miroslav Holub

An old man suddenly died

alone in his garden under an elderberry bush.

He lay there til dark, when the bees

fell silent.

A lovely way to die, wasn't it,

doctor, says the woman in black

who comes to the garden

as before, every Saturday,

in her bag always lunch for two.

trans. by Ewald Osers

POET

Miroslav Holub (1923 - 1998)

excerpt

Miroslav Holub is a scientist by vocation and considers his poetry a pastime. Holub told Stephen Stepanchev in a New Leader interview that the Czech Writers Union had offered him a stipend

equivalent to his salary as a research scientist to enable him to

devote two years to his poetry. "But I like science," he said. "Anyway,

I'm afraid that, if I had all the time in the world to write my poems,

I would write nothing at all."

Holub read his poems in 1965 at the Spoleto Festival, Italy, in 1967 at

the YMHA Poetry Center in New York under the auspices of the Lincoln

Center Festival, in 1968 at the Harrogate Festival, England, in 1974 at

Poetry International, Rotterdam, Holland, in 1975 at the Cambridge

Poetry Festival, Cambridge, England, and in 1981 at the International

Poetry Festival, Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Holub spoke English,

French, and German.

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/archive/poet.html?id=3240